In my new job, I'll start by looking the cat out of the tree 🐈 It's an animal edition! 🐒

In which I shamelessly let past me do much of the work

Welcome to the latest instalment of English and the Dutch, the newsletter with tips and tricks, fun facts, new translations and other good stuff about how Dutch speakers speak English. In your inbox every third Wednesday of every second month.

The newsletter is written by me, Heddwen Newton. I’m half Dutch, half British, and I work as a translator, teacher, and linguist. I am the owner of the website www.hoezegjeinhetEngels.nl, and the newsletter English in Progress.

Preamble

A few months ago, I was asked to write a regular column for DUTCH, a magazine aimed at Americans and Canadians with Dutch heritage. I of course said yes, because it sounded fun, and also, not unimportantly, they were going to pay me. Actual money. It almost makes me feel like a grownup!

Once the column has been published in the magazine, I am also allowed to share it with my own readers in this newsletter, so that is what I will do. The column is aimed at English speakers who are interested in the Dutch language, but don’t actually speak it. Which, you know, is not you guys. But I hope you’ll enjoy it anyway. Or just skip it and scroll down to the memes - they’re the best bit anyway!

I’m not super happy with the first piece. I tried to do a thing, give it a bit of a gimmick, and it didn’t work. But you get to read it anyway! Aren’t you lucky! We’ll do the usual quiz and etymology first, and then you can read the column. And since the column is about animals, so is the rest of this newsletter.

More actual money will be coming from my new job at a corporate training provider (I know, right? Fancy!). It will be keeping me busy, so for the foreseeable future, this newsletter is coming out once every two months.

Quiz

This Dutch speaker isn’t saying what they want to say with these sentences. What are they trying to say? What does the English speaker understand? How should they have worded it?

I found an eagle in my garden, the poor thing had a hurt foot.

When I brought it into the house, my dog Charlie wouldn’t leave it alone, so I had to put him in the bench.

Charlie was just being rowdy and playful, but I was worried he would hurt the small animal. “Stop acting like an ape!” I told him.

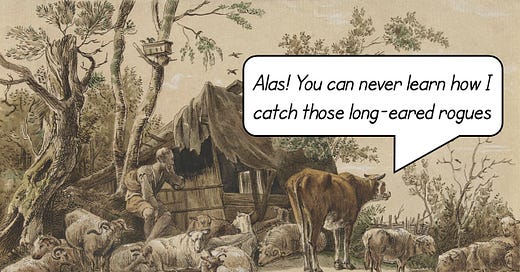

Proverb

The much-loved Dutch proverb depicted below has a very similar English counterpart. What is the Dutch proverb? What is the English one?

Family ties

Dutch and English are cousins, perhaps even sisters, depending on how you like your familial metaphors. In this section, I highlight some surprising ways in which they are related.

It is common to see memes online about those silly Dutch people and their literal words for animals. Stekelvarken, because it looks like a small pig and has spines. Neushoorn, because it has a horn on its nose. And Nijlpaard, because it looks like a big fat horse, and lives in the river Nile. Hahaha, those funny Dutch speakers!

What English speakers don’t realise is that their own words for animals are often just as simplistic; they just took a detour through languages like Greek and French.

porcupine - the word “porcupine” comes from the Old French porc-espin, “spiny/thorny pig," from Latin porcus “hog” + spina “thorn, spine.” We still see the pig, of course, in the modern English word “pork”, and the “pine” is almost literally still spine (the “thorn, prickle” sense in English is older than the “backbone” sense.)

hippopotamus - from Greek ho hippos potamios "the horse of the river". You can still see that hippo means horse in words like “hippique sports” (hippische sport), to refer to sports that use horses, and “hippodrome” (hippodroom), a horse riding track. The potamo is still evident in “Mesopotamia”, which got its name because it lies between two rivers, and “potamology”, which is the study of rivers (who knew!).

rhinoceros, from Greek rhinokerōs, literally "nose-horned," from rhinos "nose" + keras "horn of an animal". We see “rhino” for nose in many medical terms like “rhinoplasty”, a nose job, and “rhinovirus”, the most common cause for the common cold. Keras is seen in “keratin”, the stuff that makes up hair, nails, scales, feathers, hooves, and, yes, horns. It’s also in “triceratops”, the dinosaur with three horns, and “carrot”, which was so named because it was shaped like a horn!

Sources: porcupine, hippopotamus, rhinoceros, carrot (you have to go quite far back for the carrot thing, and it isn’t confirmed, but I liked it so much I couldn’t leave it out!)

Speaking Dutchly

Speaking Dutchly is my column for DUTCH, a magazine for Americans and Canadians with Dutch heritage. It is aimed at English speakers who are interested in the Dutch language, but don’t actually speak it.

When Dutch animals get lost in translation

Who doesn’t love a quaint proverb? As a linguist who specialises in the way Dutch speakers use English, I especially enjoy proverbs that Dutch people struggle to convert into English. Not because I enjoy seeing people struggle (I am an English teacher, but I’m not that cruel), but because I collect Dutch idioms that are not easily translated.

And there’s nothing quainter than animal proverbs, so let’s set a scene…

Imagine a Dutch droning bear (brombeer), a malcontent. He always looks the cat out of the tree (de kat uit de boom kijken), meaning he has a perpetual wait-and-see attitude. And he always sees bears on the road (beren op de weg zien), meaning he always sees potential problems where others see none - which makes sense, as there are no bears in the Netherlands and Belgium!

He wishes he had his sheep on dry land (zijn schaapjes op het droge hebben), which would mean he has worked to become financially comfortable, and now no longer has money trouble. But alas, he is as poor as a church mouse (zo arm als een kerkmuis*).

Aha! English has the proverb about the church mouse too! It shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise, the languages are closely related, after all. There are many similar proverbs. But I’m trying to list Dutch proverbs that do not have an easy equivalent, so let’s return to our curmudgeonly hero.

He looks in the mirror and thinks to himself: even if a monkey wears a gold ring, it will still be an ugly thing (al draagt een aap een gouden ring, het is en blijft een lelijk ding). He will never be good looking. He once paid money for a facelift, but it turned out he had bought a cat in the bag (een kat in de zak kopen); he had made a bad investment.

Feeling down, our grouch comes home in the evening, only to find that dinner has been and gone. He has found the dog in the pot (de hond in de pot vinden). The Dutch love this idiom because it gives them a mental image of a dog sitting in a pot, but actually it refers to the dog licking out the pan of leftovers. If you come home to find that, you are definitely too late for dinner!

To add insult to injury, his family members had been having a party. After all, our sourpuss thinks, as the saying goes: when the cat is away from home, the mice dance on the table (als de kat van huis is, dansen de muizen op tafel). When an authority stops paying attention, people tend to have a bit of fun.

Oh dear, this is all getting rather depressing, isn’t it? Let’s give our hero a happy ending.

Turns out, the party was for him! “Oh no,” his wife cries, spotting him, “the monkey is out of the sleeve!” (De aap is uit de mouw). The cat is out of the bag**! “My handsome, prudent husband, we are preparing a surprise party to celebrate you winning the lottery!”

Our hero sighs a happy sigh. It just goes to show, he thinks, you never know how a cow catches a hare (je weet nooit hoe een koe een haas vangt). Even if a positive outcome seems very unlikely, it can still happen!

Some of the proverbs mentioned above are easily translated. The Dutch monkey that was not beautified by the golden ring is easily compared to the American pig whose lipstick make-over had no positive effects. But as I said at the top, I am always especially pleased to find proverbs that do not have a direct translation into English, and I made sure to include quite a few in this column. As far as I have been able to tell, there are no good English equivalents for looking the cat out of the tree, seeing bears on the road and many of the other proverbs listed above. If you discover any, drop me a line!

*In Dutch, the church rodent can be a mouse, but it is more usually a rat. Zo arm als een kerkrat.

**The cat out of the bag and the monkey out of the sleeve are not exactly the same; see my article here.

Quiz answers

I found an eagle in my garden, the poor thing had a hurt foot.

What are they trying to say? - Ik heb een egel in mijn tuin gevonden, het arme ding had een zere poot.

What does the English speaker understand? - Ik heb een adelaar in mijn tuin gevonden, het arme ding had een zere poot.

How should they have worded it? - I found a hedgehog in my garden, the poor thing had a hurt foot.

When I brought it into the house, my dog Charlie wouldn’t leave it alone, so I had to put him in the bench.

What are they trying to say? - Toen ik hem naar binnen bracht, kon Charlie, mijn hond, hem niet met rust laten, dus heb ik hem in de bench gezet.

What does the English speaker understand? - Toen ik hem naar binnen bracht, kon Charlie, mijn hond, hem niet met rust laten, dus heb ik hem in de zitbank gezet.

How should they have worded it? - When I brought it into the house, my dog Charlie wouldn’t leave it alone, so I had to put him in the dog crate.

Charlie was just being rowdy and playful, but I was worried he would hurt the small animal. “Stop acting like an ape!” I told him.

What are they trying to say? - Charlie deed gewoon druk en speels, maar ik was bang dat hij het diertje kwaad zou doen. "Gedraag je niet als een aap!" waarschuwde ik hem.

What does the English speaker understand? - Charlie deed gewoon druk en speels, maar ik was bang dat hij het diertje kwaad zou doen. "Gedraag je niet als een mensaap!" waarschuwde ik hem.

How should they have worded it? - Charlie was just being rowdy and playful, but I was worried he would hurt the small animal. “Stop acting like a monkey!” I told him.

Though most English speakers would probably interpret the above correctly in this context, and the words used to be the same, it is still important to know that the word “ape” in English only refers to primates such as chimpanzees, gorillas, and, indeed, humans. “To act like an ape” might therefore also be interpreted to mean “to act inquisitively, to show intelligence”. It might also be taken to refer to the verb “to ape”, which means to copy someone, just like na-apen in Dutch.

All this means that when you are translating the Dutch word aap, you have to decide if you are talking about a “monkey” or an “ape”.

(I learned so much about monkeys while researching this. Did you know that it is not quite true that monkeys have tails, and apes don’t? There are, apparently, quite a few tailless monkeys. And did you know that monkeys from the Americas are a different set of species from the ones in Africa and Asia, and that one key difference is that the American monkeys can use their tails to grab things? Handy!)

Proverb

Als de kat van huis is, dansen de muizen op tafel.

When the cat’s away, the mice will play.

And finally…

And finally, a silly joke, funny video or interesting picture that I found on the Internet, that has something to do with Dutch, English, or the newsletter’s theme.

Three silly jokes, this time!

(This should have been “Oh, good, you brought the interpreter”, of course!)

What is the word “huisdier” in English? Think about it…. Think about it… Yes, you’ve got it! Groaning is allowed!

Automatic translation gone wrong!

Get free postcards

If you get ten people to sign up to this newsletter, I will send you ten funny postcards with texts like “I stick you a heart under the belt”, “heartily thank” and “hurray, you are yeary!”

Get just three people to sign up, and you get access to a page with cartoons, jokes and memes about the English language. (With explanations, because I hate it when I don’t get a joke.)

Use the button below to get a special link that you can share via email or on social media.

Get this newsletter two days early

Any mistakes in this newsletter were put in by me AFTER my four amazing feedbackers checked through it. Thank you, you wonderful people!

Would you also like to receive this newsletter two days early? Then reply to this email and become a feedbacker! You don’t have to be a professional proofreader, I’m happy to hear any and all remarks. Perhaps you didn’t understand something, or you thought of an extra joke to put in somewhere, or you happen to know an extra piece of etymology that I missed. I’d love to hear from you!

This comment isn't specifically about the current edition. On some other page, which I can’t find again at the moment, you speak of our tendency as native speakers of English to go all hypercorrect when explaining pronunciation to speakers of other languages. The example given was clothes /klouðz/ vs /klouz/. So anyway I thought you might be amused by this illustrative verse from the very obscure “Songs of the Pogo“, 1956. In the song _Whither the Starling and Whither the Crow_, Walt Kelly wrote the following: “the weaver‘s wet daughter has dampened the clothes / with wavelets of water left over from snowthes“.

>bought a cat in the bag (een kat in de zak kopen)

We do have "bought a pig in a poke", but I suspect that a lot of people don't know that "poke" here is an archaic word for a bag (related: "pocket"). In any event, "pig in a poke" might not be that common anymore, dunno.

re: porcupine. I like our tendency to name unfamiliar animals with more familiar names. As you note, "pig" is one of those kinds of ur-animals, at least for naming purposes. In German (and Old English), as you know, a porpoise is a Meerschwein. Plus we have aardvark (Dutch), hyena (Greek "hys" for "pig"), guinea pig, hedgehog, and and groundhog. If a new animal is big, it's a type of horse; if it's small, it's a kind of pig. :)